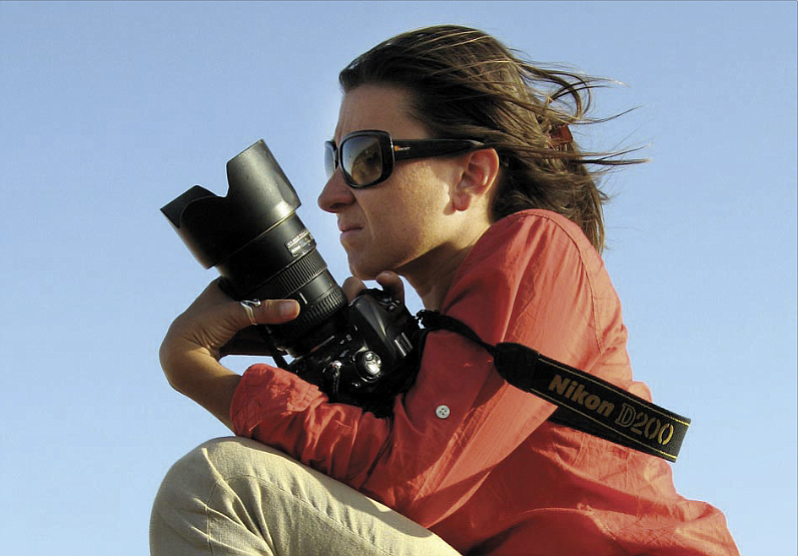

The fearless Lynsey Addario speaks at Tarleton about being a photojournalist in war torn countries

Photo courtesy of http://www.lynseyaddario.com

A Rohingya family, Burmese Muslims, live in the Thay Chaung camp for the Internally Displaced outside of Sittwe, which houses nearly 3000 people, November 23, 2015. The mother, pictured here, claimed all her children were malnourished, but because of the lack of medical professionals in the area, it was impossible to confirm. An estimated one million stateless Rohingya have been stripped of their citizenship in Myanmar, and forced to live in modern-day concentration camps, surrounded by government military checkpoints. They are not able to leave, to work outside the camps, do not have access to basic medical care, or food. Most aid groups are banned from entering or working in the camps, leaving the Rohingya to their own devices for sustenance and healthcare. Journalists are also routinely denied access to the Rohingya, Myanmar’s way of ensuring the world doesn’t see the slow, intentional demise of a population.

April 11, 2018

Photo courtesy of http://www.lynseyaddario.com

Photo courtesy of http://www.lynseyaddario.com

Lynsey Addario has been kidnapped twice, been ambushed by the Taliban and is one of the few photojournalists who has experience working in Afghanistan. However, no matter what she has faced it has only help drive her passion to cover the war and other humanitarian issues.

Addario is an American photojournalist. Her work often focuses on conflicts and human rights issues, especially the role of women in traditional societies. Although Addario’s work is mostly freelance she regularly works for The New York Times, National Geographic and Time Magazine.

Addario started taking pictures at 12 or 13 but it was always a hobby. She then when and studied international relations in italian at the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

“When I graduated I wanted to move to Argentina to learn spanish,” Addario said. “I went down there and I started becoming aware of pictures at the local newspaper, The Buenos Aires Herald, in Argentina. I realized that photos are a way of telling stories and incorporating my studies with politics and international relations and how to tell those stories in a compelling way.

“Photojournalism is a marriage of an art and storytelling.She stared at the Buenos Aires Heraldfor 10 months learning how to be a photographer and then I moved to New York where I freelanced for the New York Daily News and the Associated Press and stayed there for four years freelancing and learning and getting mentored.”

It was after working at the Associated Press that she began to work in places that were classified as unsafe or conflict areas.

“My interests was always overseas and I was always interested in covering other cultures and to understand, to bridge cultures,” Addario explained. “So to understand what life was like in countries particularly where we had very little information and where we had misconceptions about population. So for example, in 1997 I started going to Cuba. That was because Cuba was illegal for Americans and so instead of thinking that all Cubans were evil I thought well why not just go there and figure it out and talk to Cubans and see what they are like. Of course they were lovely and funny and great. What you don’t know, you assume evil but once you get there you realize it’s actually that they are just like us. That has always been my philosophy.

“So when I was working at the Associated Press in the 90s I was traveling back and forth to Cuba every year and then I moved to India in 2000. I had the opportunity to go to with a family friend and I thought well why don’t I just move there. So I moved there to be a freelancer and that’s when I started working in Afghanistan. I didn’t seek out war zones but I was curious about situations and it just so happens that a lot of those humanitarian and human rights issues happened to be in war zones and they happen to be on the margin or repercussions of war. So I would just sort of go. I was just very curious and felt very strongly about bearing witness for myself.”

While Addario was out at these countries taking photos for her jobs she has had some scary experiences along the way. The most terrifying experience so far for her being when she was kidnapped in Libya which happened in March of 2011.

“I’ve been kidnapped twice and both of those times were pretty terrifying,” Addario explains. She recommends reading her book to see why someone like her continues to do this work even after all that she has gone through it also goes more in depth about her experience.

“So I started covering conflict in 2000 while it was under the influence of the Taliban and I was 26 years-old and saved my money to see what was life like under the Taliban and see if it was as bad as we speculated,” Addario said. “This was before September 11, before there was combat and fighting. Ironically it was pretty safe under their rule. She went in after 9/11 to cover the war and cover the fall of the Talibanand then went in to cover Iraq.

“In 2004 was the first time I was kidnapped in Fallujah, Iraq. Which was a Sunni stronghold and the guys that captured us had links to Al Qaeda. That was terrifying obviously because we were driving into this hostile area rounded and corner and then entire road was full of insurgents with there faces wrapped guns and rockets and they started shooting in the air and I was pretty sure we were going to die. We were held for about six to seven hours and at dusk they let us go because were were able to convince them that we were journalists and we were there to tell their story and we had no sort of tie to the American troop. We were just there to tell the story of the war.

“Although in 2011 we were not as fortunate. We were covering the Arab spring and the uprising in Libya. The front line we were covering got over run by Gadhafi’stroops and we ran into one of Gadhafi’scheckpoint. Our driver was killed and we were taken and held along the front line for the first three days where we were beaten up, tied up, blindfolded, groped, put in prison and threatened with execution. Eventually we were flown in a military aircraft to Tripoli where we were under house arrest for another three days until we were released. It was really scary. We had guns to our heads most of the first three days and at one point they had us face down in the dirt and were about to execute us, it was really scary.”

With everything that Addario has been through she has some significant accomplishment.

“Lynsey’s recent bodies of work include “Finding Home,” a year-long documentary following three Syrian refugee families and their stateless newborns over the course of one year as they await asylum in Europe for Time Magazine, “The Changing Face of Saudi Women” for National Geographic Magazine and “The Displaced” for the New York Times Magazine, a reportage documenting the lives of three children displaced from war in Syria, Ukraine and South Sudan,” Lynsey Addario website states. “Addario has spent the last four years documenting the plight of Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq for The New York Times, and she has covered the civil war in South Sudan, and Maternal Mortality in Assam, India, and Sierra Leone for Time Magazine.

“The MacArthur Program awarded Addario the 2010 Fellowship for photographic essays on Afghanistan and Iraq depict the underlying realities of war: the pain, confusion, and exhilaration of being a soldier; the daily struggles for civilians, especially children, living in a war zone; and the lives of Taliban leaders. As well as Addario’s work is capturing the lives of women in male-dominated societies.

“Addario was awarded the Pulitzer Prize as part of the New York Times team for International Reporting. Her photographic work was part of the New York Times coverage of the war in Afghanistan for the magazine cover article Talibanistan, Sept. 7, 2008.”

On top of all these accomplishments and adventures that Addario was on, she wrote a book called “It’s What I Do: A Photographer’s Life of Love and War.”

“I loved writing because when I wrote it I had spent almost 15 years shooting nonstop and I had never really looked back at all,” Addario explained. “I was just obsessed with just photographing and telling the stories. I had never really stopped to process all the things I had seen and learned and the experiences from Afghanistan, Iran, Darfur, Congo, Libya and Lebanon. When I sat down to write the book, I wasn’t going to it wasn’t something I had originally sat down to do but I meet this literary agent who basically just convinced me that I had a great writing voice and that I had a really interesting story to tell. When I sat down to do it I just loved it and it was nice to use my creativity at home and download all of these little vignettes that I had been holding on to for so long. It gave me a chance to look at old email and letters I had written and look at old photographs and unedited photographs. It was emotional writing the book I felt myself weeping into the computer.”